The first classified telephone directory in 1878 consisted of a single piece of paper by the New Haven District Telephone Company in Connecticut. The fifty subscribers paid to have their names and addresses listed in the directory. The legend of how the pages became yellow five years later would seem to stem from a Cheyenne, Wyoming printer who ran out of white paper. Regardless, research indicated that black type on yellow paper was easier to read than black on white. A well-known fact to many subsequent graphic designers. It also served to separate the white residential listings from the yellow business listings.

R.R. Donnelley & Sons Company was founded in Chicago in 1864 by Richard Robert Donnelley. His son, Reuben H. Donnelley, founded the otherwise unrelated company formerly known as R. H. Donnelley. Reuben established the first official telephone directory in 1886, creating an entire industry that would become known as the Yellow Page Directory. Initially, they were the exclusive monopoly of R. H. Donnelley and the telephone companies. In 1917, the company was incorporated and moved to New York City though they kept their Chicago operations. When Reuben Donnelley died in 1929, the company continued to contract with the Bell System to publish telephone directories nationally. By 1961, R. H. Donnelley became a wholly owned subsidiary of Dun & Bradstreet.

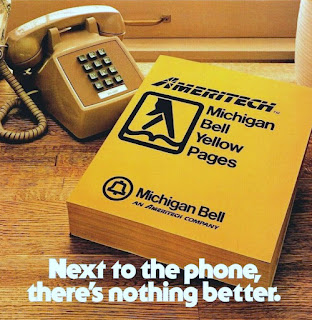

Note: By the turn of the twentieth century, the telephone served as the only technology that could be used to contact anyone in the world in real time and only accessible through the Yellow Page directories. The newest phone books—delivered free—were an indispensable item for home and business owners. The dot com boom meant that the yellow page days were numbered. 2009 marked the death of the yellow page directories with the bankruptcy of R. H. Donnelley.

A thorough history of the Yellow Page directories can be found here.